Misinformation, alongside climate change, exists as one of the greatest threats to our planet today. We live in a world where your second aunt's third cousin can share a post on Facebook about their hangover cure, and do so with the same perceived authority and trust as The Lancet. And because social platforms are geared to show us more from the people we interact with and care about most, that means that some of those opinions will bubble their way to the top. Death to water, viva la fry up.

Fortunately though, a great many of these situations are harmless.

For example, as a child I was told that the way to tell the difference between a male and female seagull was whether they 'wore lipstick' (the red part present on some of their bills).

Turns out, this was a complete, if rather wholesome, lie.

The problem is that, delighted with my little bit of random trivia, I proceeded to - over a number of years, including as an adult - tell people this little anecdote. And, having stated it with such confidence, I'm sure that at least 100 people have heard this from me, and believed me. Indeed, I've heard some of those people tell others, and point at me as 'the seagull guy' who blew their minds with my knowledge of seabirds. Because of me, with network effects, there are potentially thousands of people who hold this belief.

It's not quite what I hoped to be remembered for, but here we are -- because misinformation works in much the same way as the high school rumour factory does.

Pick a subject that's open to lots of opinion or at least slightly complex, and present something that makes it easy to understand, easy to agree with, and state it with confidence. Congratulations, you've created misinformation. In 90s home shopping network fashion, "It's Just That Easy!"

For example, remember that time when a hastily-written "legal-sounding" paragraph was copy/pasted across everyone's social profiles? Or how about when George Takei died for the 129th time? It's incredibly easy to turn false facts into gospel by simply saying it to the right people, and being remotely likeable to them.

Thankfully, nobody's going to end up in trouble over seagull gender politics, a Facebook status of legalese or a not-dead Star Trek actor. If anything, someone might pull you up on it, and you'll have a laugh.

The issue though is that the same person who says something stupid, beautiful or fun that goes viral, can equally say something truly awful -- because the unfortunate truth is that we all have the power to say and do awful things.

Consider the following quotes, from the same person:

"Our mind is all we've got. Not that it won't lead us astray sometimes, but we still have to analyze things out within ourselves."

"My main interest right now is to expose the Jews. This is a lot bigger than me. They're not just persecuting me. This is not just my struggle, I'm not just doing this for myself... This is life and death for the world. These God-damn Jews have to be stopped. They're a menace to the whole world."

The above, both from the late chess grandmaster Bobby Fischer, came some time apart -- and is reflective of someone who's anti-semitism and vile views on a range of subjects became increasingly aggressive as time caught up, and a mix of undiagnosed and unresolved mental health issues continued to grow.

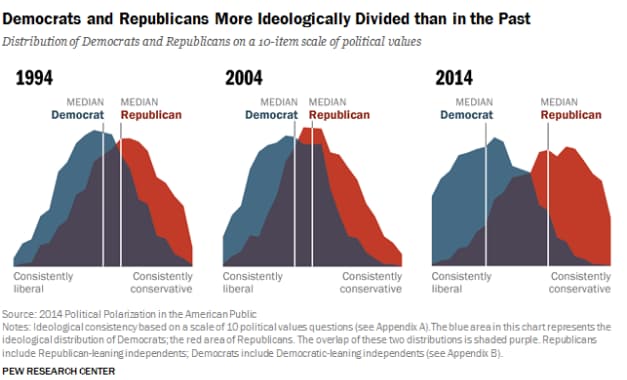

If these were posted today, Fischer could've won fans over with the first quote -- and while he'd likely have alienated many with the second, many would've believed it as fact and agreed because of who said it. This is the power that we currently give to the people we care about, admire, or respect in 2021. As a society, we're far more willing to believe what the people we like say. This is an insidious issue that affects everything we do as a society, including our politics and views of each other. Consider the below graph, showing the growing loss of consensus and middle ground in US politics.

Without consensus, discourse and middle-ground -- coupled with an increasingly tribal society -- misinformation is able to spread with far greater ease. It's no longer seen as acceptable to be wrong -- and even the fact checkers struggle to confront this. Evidence can be instantly ignored or discredited through the simple phrase 'fake news'.

In short, once an opinion is formed, it's harder than ever to change it. That's why it's vital that we take steps to stop it being spread at the source. And the unfortunate truth is that ad tech has played a large part in this -- even those once seen as allies in solving this problem have been found guilty of ensuring finance reaches some of the most prominent proponents of misinformation. Together as an industry, we need to take action urgently to deplatform these harmful opinions.

Through the rise of tools such as automated fact checking through FullFact, platforms have more options than ever to assess publishers for compliance. It's time that the key platforms start paying attention to editorial, not just impression volumes and whether a tag works.

Straight up deplatforming has been shown to work in suppressing misinformation and worse, but carries the risk of simply pushing more people into the shadows. New decentralised social networks like Mastodon have experienced this acutely. As a network, they operate a 'Fediverse', whereby thousands of small communities can all cross over and interact with each other -- consider it to be like if Reddit and Twitter made a mix tape.

Through thousands of smaller groups instead of large central communities, it then becomes possible to censor and oust far-right views and misinformation quickly. Small groups which support it will be crushed by the larger, and within small groups people can be more vocal in challenging it.

The issue here, though, is that as it's decentralised, once it arrives on the platform. It can be incredibly hard to root out -- and doing so would then put it in sharp conflict with its goals and missions. It effectively becomes the opposite issue to Facebook -- instead of a centralised power who moderates, they've empowered the users to do the work. As such, as more extreme views enter over time, the barometer of what's accepted in the group shifts -- potentially becoming an even worse mess.

The solution, therefore, needs to be removed from platforms, and come from the top -- our lawmakers. Specifically, we need legislation and independent auditing of communication to communities of any sort of significant size. For example, a weekly newsletter with 10,000 readers has significant risk if sharing misinformation.

Integration with automated independent fact-checking services can make this process quick -- it needs to become a legal requirement to screen communications for misinformation prior to sending, with enforceable fines for misinformation with harmful outcomes, e.g, Holocaust denial, or aggressive COVID anti-vaxx scares. But of course, it needs to do it without becoming an Orwellian hellscape. It's a thin line.

However, if a solution is financed by the offenders-in-chief -- negligent ad tech vendors and social media platforms -- and stewarded by a representative collective of our society as a jury of the internet, we could start to turn the tide and clean up the internet for good.

Because some seagulls do wear lipstick.